Finding Your Roots

Westward Bound

Season 12 Episode 6 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

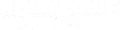

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. heads west to map the family trees of Sara Haines and Tracy Letts.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the family trees of talk show host Sara Haines and playwright Tracy Letts—tracing their roots from frontier towns in the American west to diverse places in the east, telling stories of scoundrels, soldiers, and U.S. Presidents, while also discovering surprising connections to Native Americans communities—revealing the complexity at our nation’s core.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Westward Bound

Season 12 Episode 6 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the family trees of talk show host Sara Haines and playwright Tracy Letts—tracing their roots from frontier towns in the American west to diverse places in the east, telling stories of scoundrels, soldiers, and U.S. Presidents, while also discovering surprising connections to Native Americans communities—revealing the complexity at our nation’s core.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Welcome to “Finding Your Roots”" In this episode, we'll meet talk show host Sara Haines and actor and playwright Tracy Letts, two people whose ancestors made truly surprising journeys.

HAINES: So he's the first one here?

GATES: You just met your original immigrant ancestor on this line of your family tree.

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

GATES: That is almost 300 years ago.

HAINES: That's crazy.

LETTS: Born: 1782.

GATES: That's right.

LETTS: I wonder what was going on with these people?

(laughter).

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

HAINES: Wow.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

LETTS: How the hell'd you people find this stuff?

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a “Book of Life...” (gasps excitedly).

GATES: A record of all of our discoveries.

HAINES: Is it weird, I'm already crying?

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

LETTS: I didn't know any of this.

My questions were met for all of my childhood with a shrug.

“We don't know.” GATES: You had no idea?

HAINES: None of these things, I know nothing of this.

(laughter).

I have identity.

GATES: Deep American... HAINES: Deep American identity.

GATES: Yeah.

LETTS: I feel a little bit more ownership of this country.

GATES: Tracy and Sara both descend from people who came to North America long before the birth of the United States.

In this episode, they're going to retrace the journeys those ancestors took, inspiring them to see themselves and our nation in a new way.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ (street noise).

GATES: Sara Haines has America's ear.

GOLDBERG: It's Sara's birthday.

GATES: The beloved cohost of “The View” has built an enormous fan base because she could connect to almost anyone, anywhere, with warmth and humor.

It's a rare talent, one that Sara did not initially know she had.

Sara grew up in Newton, Iowa, a small town east of Des Moines.

Her parents were both Air Force veterans, and Sara was raised to pursue pragmatic goals.

But after graduating from Smith with a degree in government, she decided to chase a dream and told her parents she wanted to move to New York City in order to try acting, a decision that was not well received.

HAINES: My dad said, I didn't send you to Smith College to be an actress.

(laughter).

And I thought, “Oh, that's a truth bomb.” But I'm grateful.

But, oh my gosh.

GATES: Yeah, but what did you say in return?

HAINES: I said, “Okay.” I mean, 'cause my dad and my mom, but my dad specifically, I have such a reverence for him.

So when he speaks, like it or not, I have deep respect for when he speaks.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: And so, in my mind, I remember thinking, “Oh crap, I, I don't break with them very often.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: This is gonna hurt regardless.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: Either I'm suppressing me or I'm disobeying in some ways them.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: And I knew what I had to do, I knew right away I was gonna go anyway.

But to look at my dad and think, “Oh my gosh, they, they gave me this whole life.” GATES: Right.

HAINES: And now I'm saying I want something else.

GATES: Sara's pursuit of that, something else would follow a very circuitous path.

In New York, she found a job, not as an actor, but as a production coordinator on “The Today Show,” where she would eventually work with host Kathy Lee Gifford and Hoda Kotb.

The show was extremely popular, but also in need of younger talent.

And Sara seized an opportunity.

HAINES: I was watching producers do interviews, but they were off-camera.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: And I said, I'll do all the research, I'll do all the work.

I'll do; I'll do your entire job for you if you let me do that interview and sit on camera.

GATES: Huh.

HAINES: So I started doing interviews for the website... GATES: Uh-huh.

HAINES: Now I'm making a reel, and I'm thinking, “Great, I can't wait to send this out to audition for things.” And Kathy Lee and Hoda were like, "Why wouldn't you come play with us?

We have this fun hour..." GATES: Uh-huh.

HAINES: And I was like, "People don't start at 'The Today Show'... ...that's where we end."

GATES: Right.

HAINES: So I asked them, I go, “What do I wanna offer you?

I'm not a trainer; I'm not a chef.

I do what you do.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: And they were like, “Teach us something, young.” (laughter).

And so they were like, "Think of something you'd teach your mom."

And so I remember the first segment I pitched was like, "How to get your digital photos and, and put them on things," like back when the mugs were starting out, and... GATES: That's pretty good.

HAINES: It's a very mom segment, you know.

So I did that, and they were like, that was fun.

And eventually I pitched changing their Facebook page because the Facebook page had 200 friends for the, the most winning morning show at the time, and we should change it.

GATES: Right.

HAINES: But this is how early it was, though, when I notified the PR at Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg's sister flew in to meet with me to design the page.

And the day that page launched, that real-time fan interaction, that was the day I started being on every day.

I'm keeping you hip, and Hoda was asking about these... GATES: That moment changed Sara's life forever.

HAINES: What fun it always is, so let's get right to it.

GATES: After five years with Kathy Lee and Hoda, she debuted as a guest host on “The View,” America's top-rated daytime talk show.

Soon she would join full-time, and now she's one of the show's longest tenured members.

But even as she's risen to the top of her profession, Sara has preserved the passion that first drew her to the camera.

In fact, she credits her success to it.

What do you think made you good at it?

HAINES: A genuine curiosity for people.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: I love hearing how people end up where they are.

I'm not trying to take your job, not ancestry, but like, I wanna know, like, do you have siblings?

Where did you grow up?

GATES: Uh-huh.

HAINES: Where are you in the birth order?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: Are you close with your family?

GATES: Right.

HAINES: What do, I wanna know what makes you tick, 'cause I know that all those things make me tick.

GATES: My second guest is writer and actor Tracy Letts, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for “August: Osage County.” One of the most brilliant plays in the history of American drama.

Tracy grew up in Durant, Oklahoma, a small city near the Texas border.

Much like Sara Haines, he comes from a close-knit family and adores his parents.

But Tracy's parents were very different from Sara's.

His father taught literature.

His mother was a writer, and Tracy was eager for their approval.

LETTS: I was an entertainer.

I liked to entertain the family.

I liked to get laughs.

I liked being the center of attention... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: ...in my family.

And according to my parents, I was, I was entertaining.

And, uh, I, and I kept things pretty light for, for a while anyway.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: But also, my parents put such great stock in artists that they just considered it kind of the highest calling.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: They wanted us to get out of Durant, Oklahoma.

GATES: Right.

LETTS: And they wanted us to have interesting lives.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: I can't tell you the number of times my mom, uh, expressed, uh, delight and satisfaction that my brother and I had not become bankers.

She considered that just sort of the... GATES: The pits, the worst.

LETTS: Just the worst.

(laughter).

GATES: Though Tracy's career choice would please his parents.

It would also lead him down a very dark road.

After dropping out of college, he moved to Dallas, then to Chicago, pursuing acting while trying to write plays.

But success proved elusive.

And Tracy soon bottomed out.

LETTS: I was hurting a lot of people around me.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: I had broken up with a longtime girlfriend, and she called my dad.

She called my dad and said, “Look, we've broken up.

This isn't about that, but I'm worried about Tracy.

You should know he's; he's not doing well.” GATES: Mm.

LETTS: And I had recently gotten into heroin, and, and my dad flew up to Chicago.

He found me.

And he said, he said, what you say?

He said, “I love you, and I'm worried about you.

And I, I hope you can get some help.

It's clear you're struggling, and I, I, I can't do this for you.

You're gonna have to do this for yourself.

I hope you can find some help.” And I had a friend who was sober, and I asked her to take me to a meeting.

I've been sober ever since.

GATES: Sobriety would prove Tracy's salvation.

Not only did it improve his work, his work came to focus on his family.

Indeed, “August: Osage County” is essentially an artistic retelling of the dark stories and deep secrets that Tracy had absorbed from his relatives.

In a different family, such a play might have been destructive, but Tracy knew his audience well.

Did that change your relationship to your mother and father once they had seen the plays when you were drawing on their trauma, in fact?

LETTS: I don't think so.

It's a funny thing, you know, people like to see themselves represented.

GATES: Yeah.

LETTS: And it kind of doesn't matter... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: How you represent in some ways, just the fact of representation... GATES: Right.

LETTS: ...is what's important.

There's a story in “August: Osage County,” a character tells about a stepfather beating, beating a child with a claw hammer.

GATES: Mm.

LETTS: The gentleman in my family, to whom that happened, came to see the play.

He was an old man; he was 80 years old.

And when the play was over, he said, “How the hell do you know the claw hammer story?” (laughter).

And I said, “Well, I don't know.

I just, you know, family lore.

I've picked it up over time.” And my parents didn't know the claw hammer story.

And they turned to him, and they said, “You got beaten with a claw hammer?” He laughed about it.

He said, “Uh, yeah.

Uh, my uncle Ray damn near killed me.” GATES: Huh.

LETTS: But he roared with laughter in the theater.

You know, he liked seeing himself represented.

So my folks weren't daunted by my representation, and they understood that as an artist, that was my job... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: ...and my right.

GATES: So, for you, playwriting is a version of writing a family history, preserving a family story.

LETTS: I think that's true.

GATES: After spending time with my guests, it was clear that Tracy and Sara have both been shaped by the values of their parents.

Now, each is about to take a journey that will forever change how they understand the origins of those values.

I started with Sara and with her father, Richard Haines.

On the surface, Sara and Richard may appear to have little in common, but they share a profound bond.

HAINES: My dad, I always described, even in my online dating profile, where I met my husband, is I said, “I'm looking for someone who, who does the right thing when no one's watching.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: Because that's my dad.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: He is a very stoic, serious person that when he speaks, you care and you wanna hear, 'cause he doesn't overpopulate the airwaves like, I am a talker.

I'm silly.

I'm always going for the moment.

Uh, I'm a performer.

He's not.

He knows what's right and he knows what's wrong, and he does those things.

GATES: Richard's confidence may flow in part from his family.

He grew up in Eastern Pennsylvania knowing that his roots in the region were deep and illustrious.

In fact, there's a prominent mill near his childhood home that his ancestors have owned since the 1860s.

But Richard had no idea where his family was before they got their mill, and Sara hoped to learn.

The answer laid deep in the past with Sara's seventh great-grandfather, a man named Jacob Hottenstein.

Jacob was born in what is now Germany, but in 1731, he's listed on a resolution passed by the Pennsylvania legislature back when Pennsylvania was still a British colony.

HAINES: “Whereas by the encouragement given by the honorable William Penn, and by the permission of his late Majesty King George I, be it enacted that Jacob Hottenstein shall be, to all intents and purposes, deemed his majesty's natural born subject of this province of Pennsylvania.” Am I royalty?

(laughter).

GATES: No, but this is the moment in 1731 that your seventh great-grandfather became a naturalized citizen of the British Empire.

HAINES: So he's the first one here.

GATES: You just met your original immigrant ancestor on this line of your family tree.

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

GATES: That is almost 300 years ago.

HAINES: I knew we'd been here a minute, but I did not know that.

That's crazy.

GATES: Jacob arrived in Pennsylvania when he was in his 20s, part of a wave of German immigration to the colony.

But court records back in his hometown suggest that Jacob was not a typical immigrant.

He was leaving a secret behind.

HAINES: “Today, the innkeeper's maid came to me and duly reported that Jacob Hottenstein had slept with her several times and impregnated her, and that she was already a quarter of a year pregnant.

Hottenstein, however, had tried to get her to abort such a pregnancy and had already brought her a handful of savon, saying that this would be quite useful, and also wanted to bring her some laurel, which others had used in the past with very good effect.” Wow, this guy slept with the maid.

GATES: In 1717, your ancestor... (clears throat) ...was accused of impregnating a woman named Maria.

Maria was a maid at a local inn.

And when she became pregnant, he allegedly tried to force her into having an abortion using that combination of herbs.

When she refused, he allegedly abandoned her.

HAINES: Is she okay?

Was she okay?

GATES: Maria was, in fact, physically okay.

But she was not happy with Jacob.

When her pregnancy was discovered, she sought help from a local pastor.

He informed the baron who presided over their town, and Jacob found himself in jail.

HAINES: Jacob went to the clinker.

GATES: He went to the, he did.

Maria was placed in a local cottage, and then an investigation was launched.

HAINES: He went to jail?

GATES: He went to jail.

Does that surprise you?

Obviously, it does.

HAINES: Well, I mean, more just the times like that, getting someone pregnant could put you in jail.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: Is just, it's just, it just feels so antiquated on so many levels.

I mean, the year was 1717.

GATES: Well, we're, we're back in antiquity.

(laughter).

GATES: So what do you imagine your ancestor had to say to defend himself?

HAINES: I, I, I don't know.

GATES: Please turn the page.

HAINES: “Special interrogation of Jacob Hottenstein, whether he knows the innkeeper's maid here.

Yes, of course.

Because he lives here.

Had he ever slept with her?

No.

He was pure, she was a wicked person.

Hottenstein confesses that the maid revealed her pregnancy to him in the meadow about three weeks ago.

And at the same time, he confesses that the maid told him that she had already eaten all sorts of things other than horseradish and yeast, but that it didn't help.

He replied that she could eat whatever she wanted for his sake; it was none of his business.” (laughter).

Oh my gosh.

GATES: Your ancestor, the, like, a typical male, denied the allegations against it.

HAINES: She's a wicked person.

GATES: A wicked person.

What's it like to see that?

HAINES: Oh, I, I hoped for better.

I hoped for like I loved her or something noble.

He sounds very shallow.

GATES: Uh-huh.

HAINES: Not a lot of character here.

GATES: Who was selling the truth?

HAINES: I think Maria was.

GATES: You think Maria was?

HAINES: I'm gonna go with Maria on this.

GATES: Sara's intuition proved correct.

After a witness came forward to corroborate Maria's story, Jacob admitted to having had a relationship with her and was forced to face the consequences.

HAINES: “According to the documents discussed and the minutes kept, it is clear that Jacob Hottenstein was the perpetrator of the impregnated innkeeper's maid.

The gracious lordship has finally graciously resolved to release him in return, for which he must pay a fine of 30 guilders.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: “And also pay the child five guilders annually for 10 years for its alimony and livelihood.” She had the baby!

GATES: She had the baby.

HAINES: Wow.

That is bonkers.

GATES: As it turns out, Maria did not just have one baby.

She had twins, and she would go on to marry a farmhand and give birth to 10 more children.

As for Jacob, he seems to have escaped his responsibilities by heading off to Pennsylvania.

GATES: What's it been like to learn this story?

HAINES: It's like, it was mind-blowing just to know these people exist, but when you look at their names next to these years, you just see these in your head, these old visuals of people that led proper lives.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: You know, it's a different time.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: And it, it reminds you that they were always just human, just of a different time.

GATES: Yeah, and passionate.

They had feelings.

HAINES: They had romps in meadows.

GATES: This isn't the, you know, when you studied the history of immigration... HAINES: Yeah.

GATES: ...to the United States.

HAINES: This is not what we learned of.

GATES: Not in the school books.

HAINES: No.

GATES: Though Jacob May have immigrated under a cloud, his family would flourish in their new country.

Indeed, his son David would help to found our nation.

David is Sara's sixth great-grandfather.

He was born in Pennsylvania around 1734, and he was roughly 40 years old when the American Revolution broke out.

That was old for a soldier.

But David joined a patriot militia.

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

Wow, that's really cool.

(laughter).

I am deeply American.

GATES: You are deeply American.

And deeply German too.

HAINES: Oh, gotta bring that German back.

GATES: Yeah.

HAINES: I don't know how much I wanna be with Jacob right now.

GATES: No, no.

HAINES: I'd much prefer his son.

GATES: Unfortunately, this story was about to take a somber turn.

While David may have been a patriot, a tax register from the year 1779 shows that he was also something far less noble.

HAINES: “Hottenstein, David, 200 acres of land.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: “Six horses, one bound servant, and one slave.” GATES: One slave.

Have you ever contemplated even the possibility that your ancestors may have been enslavers?

HAINES: I think so, uh, not under understanding necessarily why, or having a mental explanation other than if we've been here a long time... GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: ...in this country, and slavery was such a huge part of the economy of the country.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: That the likelihood, I mean, it's kind of, you hope it doesn't, you hope you're one that wasn't that way, but if even hearing that they had mills and property and land, and I kind of started to see a trend that... GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: Yeah.

GATES: Pennsylvania would begin to abolish slavery in 1780.

And it appears that David relinquished his human property soon after.

But even so, the very fact that he'd owned another human being at all left Sara struggling to make sense of her ancestor.

HAINES: It, it's almost unfathomable as much as you're going back in history and you know, that the world was a different place, the country was a different place, it's, it's it, you know, here people are flocking for opportunity for something better, to create a life, to maybe dodge their own mistakes, and yet they're going to own a human.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: On, like, I, I, it doesn't, um, track.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: It's not consistent.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

But what this shows is that family history's complicated.

HAINES: Yeah.

GATES: You know?

There are no saints and no, no devils purely, you know?

HAINES: No, no.

GATES: Like Sara, Tracy Letts came to me knowing nothing about an entire branch of his family tree, but for a very different reason.

Tracy's mother, Billie Dean Gibson, had often claimed to have Cherokee ancestors.

But in Oklahoma, long the home of various native peoples, such claims are common and usually wrong.

And Tracy and his brothers never believed them.

But our researchers uncovered an obituary for Billie Dean's great-grandfather, a man named Jack Burgess.

And it suggests that Billie Dean knew what she was talking about.

LETTS: “An old timer gone.

Jack S. Burgess was buried at Oaklawn Cemetery Sunday.

He was well known here, where he had resided the greater portion of his life.

He was a Cherokee Indian.

As a boy and young man, Jack Burgess chased the deer buffalo and wild coyote over the site of the present city of Tulsa.” GATES: So your family lore, appears to have been true.

According to that article, your great-great-grandfather was Cherokee.

What's it like to see that in black and white?

LETTS: Well... (laughs).

It's great, my mom is taking her revenge for all the teasing we gave her over the years about saying that she had Cherokee blood.

I'm telling you, anybody who's from Oklahoma claims Cherokee heritage, and it so often turns out not to be accurate.

(laughter).

And so my mom used to claim it, and we teased her about it as if it were not true.

And it turns out Jack Burgess was a Cherokee Indian.

GARY: Tracy's mother would've been pleased to know that Jack Burgess was not her only Cherokee ancestor, not by a long shot.

In fact, we were able to trace her indigenous roots back to a man named William Burgess, who was born in the 1780s in what we now call the Old Cherokee Nation, an immense tract of land in the southeastern United States.

William is Tracy's fourth great-grandfather, and the first of his ancestors to settle in Oklahoma.

But the story of how he got there is agonizing.

In 1830, the United States government initiated what became known as the Trail of Tears, the forced removal of roughly 60,000 native people from their traditional homes in the eastern and southern United States to a new territory in the west.

A harrowing journey of more than 800 miles.

For the Cherokee, the forced removal began in 1838, but curiously, we discovered that William was willing to leave long before that.

LETTS: “Muster roll of Cherokee Indians who enrolled to immigrate west of the Mississippi River under the direction of Benjamin F. Curry.

1831 December the 12th, William Burgess, total in party 10.” GATES: Any idea what you're looking at?

LETTS: Not really.

GATES: This is a list of Cherokees who signed up to leave voluntarily the Old Cherokee Nation and move westward in 1831.

LETTS: Oh, wow.

GATES: And if you notice the date, this is before the Trail of Tears.

LETTS: Before the forced removal, some government official comes out and says, who wants to sign up for this?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

And they say, we do.

LETTS: Why?

GATES: We can't answer Tracy's question definitively, but we do have a theory.

William appears on this list with at least nine other members of his family.

They were among the first Cherokees to make the journey west.

And we believe that they left willingly because they prefer to take control of their own destiny rather than wait for the federal government to compel them.

LETTS: Wow.

That's really interesting.

GATES: It is, isn't it?

It's fascinating.

LETTS: Yeah.

GATES: And it wasn't likely as brutal as the journey made by the thousands... LETTS: Right.

GATES: ...forcefully removed several years later.

But still, it was by no means easy.

They likely traveled for several months, likely mostly on foot, for hundreds of miles.

LETTS: Right.

GATES: Can you imagine?

LETTS: No.

GATES: At least they were in the spring.

LETTS: Yeah.

GATES: You have deep Cherokee roots in modern-day Oklahoma.

Did you ever imagine that this branch of your family had been there so early?

LETTS: I don't suppose I did imagine that, no.

The, the fact that this has not really been passed down in any kind of, uh, solid way through my, through my family history, through, through verbal history.

I don't know, like I say, we teased mom about her “Cherokee...” GATES: Right.

LETTS: Cherokee heritage.

She used to play into the joke too.

She'd say, well, my great-great-grandmother was a Cherokee princess, or whatever.

You know, she played into the joke.

GATES: But what's your theory?

How could this knowledge be lost?

LETTS: I don't know.

I suppose along with assimilation, we're talking about moving from chasing the deer... GATES: Yeah.

LETTS: Uh, into the "civilized world."

Maybe along with that assimilation also comes... GATES: Obliteration.

LETTS: Obliteration.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Shame.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Code switching.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Right?

GATES: Yeah.

LETTS: This is an act of imagination to even try and think of what that must be.

GATES: But we can only imagine, we can only speculate, 'cause we don't know.

LETTS: Right.

GATES: You know?

Though we'll never know what Tracy's ancestors were thinking, we were able to glean a little more insight into their lives.

In the National Archives, we uncovered what was called a “spoliation claim,” which William Burgess filed in 1842.

It describes the property he left behind in the east, hoping that he might be compensated for its loss.

The claim was denied by the federal government, but it contains a detailed list of all that William owned.

LETTS: So he's living in this situation, in that Eastern Cherokee territory.

GATES: Right.

LETTS: And he gives this up... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: ...in order to make the move... GATES: Mm-hmm, in advance of the Trail of Tears, 'cause he sees the, which way the wind's blowing.

LETTS: And then after he makes the move... GATES: He files a claim.

LETTS: He files a claim.

GATES: Right.

LETTS: Saying, “I gave all this up.” GATES: Right.

LETTS: And they say, we're not paying that claim.

GATES: No, 'cause you did this voluntarily.

LETTS: Wow.

GATES: He lost it all.

What's it like to learn this, realizing that it directly affected your own ancestors?

LETTS: Well, I'm not surprised by that.

I'm, my anger over the treatment of native peoples in our country, uh, isn't changed by this information, though I do suppose I have a little more ownership of that anger in a way, right?

Just in the evidence of it.

But the truth is, wrong is wrong.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Wrong is wrong, whether you are related by blood, by heritage, wrong is wrong.

GATES: There was one more beat to this story.

We uncovered an application for membership in the Cherokee Nation filed by one of William's sons in the year 1906.

It not only lists the tribal names of William and his wife, it also lists the names of William's parents, adding yet another level to this branch of Tracy's family tree.

LETTS: Wow.

GATES: You now know the names of your Cherokee ancestors going back to your fifth great-grandparents, in a continuous line.

LETTS: That's more information than I expected to get.

GATES: Hmm.

LETTS: And I want to call my mom, but she's dead.

GATES: Yeah.

LETTS: So I can't, but it's, I want to tell my mom it's all true.

GATES: Yeah.

I'm sorry, Mama.

LETTS: Yeah, right.

Sorry, we teased you about it.

Yeah, it's great.

GATES: What is that added identity, as it were?

How do you process that?

How does this fact complicate you?

LETTS: You know, I, a couple of my plays, “August: Osage County,” and, uh, my play, the “The Minutes,” my most recent play, take on at least partly characters of Native American heritage.

And there's always some question, especially very contemporary playwriting, who gets to tell the story... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Right?

That's a question that we're often met with.

Now, I'm not gonna go take this book out and put it on the rehearsal table and say, I get to tell this story.

And yet I admit that the sense of connection with that, uh, that family line, it's evocative for me because of the stories that I've told and the, and the stories that have been told me simply about growing up in Oklahoma.

GATES: Right.

LETTS: So, I don't know.

It brings up a lot of things, a lot of feelings.

GATES: We'd already traced Sara Haines's father's roots back more than 300 years.

Now turning to her mother's family tree, Sara was worried we wouldn't get nearly so far.

Sara's mother, Sandra May Haines, grew up in Neodesha, Kansas.

A tiny hard scrapple community, and Sara didn't expect that we'd be able to learn much at all about Sandra's ancestors.

But Sara was in for a surprise.

The story begins with her great-great-grandfather, a man named Michael Stoner.

We found Michael in the 1860 census living in Illinois on the eve of the American Civil War.

A discovery that raised a compelling question.

Have you given much thought to how the Civil War may have affected your ancestors?

HAINES: No, please tell me there are no more slaves.

(laughter).

Well, Michael would've been about 32 years at the time.

HAINES: Okay.

GATES: Which side?

You gotta guess.

HAINES: Please God, just go with the north.

Please, please, please.

If I've done anything right in my life, I'm gonna go with please the North.

GATES: Okay, please turn the page.

(laughs).

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

GATES: He joined the Union Army.

He made the right decision.

I knew I had good people somewhere.

(sighs).

GATES: Well, wait, but you had a patriot, too, remember?

HAINES: We also had a slave.

So we're, we're, I just feel so much better right now.

GATES: Michael would prove to be well worth Sara's admiration.

Not only did he volunteer for the Union Army, he reenlisted after his first term and served through the end of the war.

And then when the fighting stopped, Michael did something even more remarkable, something that would change the trajectory of his entire family.

In 1872, Michael moved his wife and their six children, roughly 500 miles west, to purchase land in Kansas near what is now Neodesha.

It must have been a grueling journey.

And its end brought sorrow.

Michael's wife passed away soon after arriving, but Michael was not to be deterred.

In 1880, he got married again to a fellow settler named Nancy Burket.

And the two started a new family, a family that began with a girl named Lulu Stoner, Sara's great-grandmother.

And of course, she was followed by your grandmother, Alberta, in 1918.

And then your mother, Sandra, in 1941.

That's the lineage right there.

HAINES: Wow.

Wow.

GATES: And you never heard any stories about this?

HAINES: No, no, not anything about how they got there.

I, some of the names, the, the Stoner last name I knew.

GATES: Right.

HAINES: But nothing else.

GATES: What's it like to know that you come from these people?

These people are tough.

HAINES: This tracks for my mom, like the whole Kansas, like out in the country, you know, fighters, survivors.

That's definitely my mom.

GATES: Yeah?

HAINES: Yeah.

GATES: Kansas posed an array of challenges to Sara's family, but it also offered opportunities.

And the move seems to have transformed Michael.

Records showed that he'd worked as a blacksmith in Illinois, but in his new home, he demonstrated a wide array of talents, as evidenced by a large number of newspaper articles.

HAINES: “The appointed officers at Neodesha, for the ensuing year, are M.C.

Stoner, Street Commissioner and Marshall.” Well, hello.

(laughs).

And then “April 30th, 1875 County Court M.C.

Stoner was appointed Constable for Neodesha Township.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: We are going places now, “November 19th, 1875, Township Officers, Neodesha Justices M.C.

Stoner.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: “September 5th, 1879, M.C.

Stoner has been hired by the Citizens and City Council as Marshall and night Watchman.” That sounds like, “Game of Thrones.” “Mr.

Stoner will make the best man we have had in this capacity.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

HAINES: “August 14th, 1885.

M.C.

Stoner has been appointed police judge by the city council.” GATES: How about that?

You never heard anything about this?

HAINES: Nothing.

GATES: Your great-great- grandfather did not stay a blacksmith for very long.

Once he got to Kansas, he changed his life.

He held the titles of Justice of the Peace, Conveyancer, Marshall, Night Watchman, and Police Judge.

And that's in just a handful of the newspaper mentions that our team found; we found a lot more that we just didn't have time to show you.

HAINES: Wow.

GATES: Isn't that amazing?

HAINES: That's really cool.

GATES: You had no idea?

HAINES: None of these things are track.

I know nothing of this.

I'm so impressed right now.

GATES: Sara was about to become even more impressed, shifting to another branch of her mother's family tree.

We traced back from Kansas to Colonial Massachusetts and introduced her to a man named Henry Adams.

Henry is Sara's eleventh great-grandfather; he settled in Boston sometime before the year 1640.

And when we mapped his family tree, we saw that it connects Sara to a very significant person.

GATES: You know who that is?

HAINES: He looks like a lot of people in my history book.

GATES: That is the second president of the United... HAINES: That's John Adams?

GATES: That is John Adams.

He is your third cousin, nine times removed.

(laughing).

HAINES: Oh my God.

I'm related to a president.

And he was a good one.

GATES: He was a good one.

HAINES: They weren't all.

GATES: He was a good one.

HAINES: Oh my God.

GATES: Sara's link to John Adams also links her to his son, the sixth president of the United States, John Quincy Adams.

These two presidents are not the only notable figures on the Adams' line.

Sara is also related to the famed patriot, Samuel Adams, signer of the Declaration of Independence.

HAINES: Him too?

GATES: Him too.

(laughter).

HAINES: I feel like I'm getting punk'd.

GATES: It's for real.

What's your mother gonna say?

HAINES: I hope my mom feels a deep pride in hearing all this, ‘cause coming from so little and not being able to pass on much in knowledge or pictures or stories because of, you know, they were just trying to eat.

You know, like that was all they did.

GATES: That's important.

HAINES: It's important.

But none of this to know this is all behind and comes through her.

I mean, I mean, I, I don't think my mom ever felt good enough for my dad... GATES: Yeah.

HAINES: ...'cause my dad came from such a different background.

GATES: Uh-huh.

HAINES: To know this was what my mom had the whole time, wow.

GATES: We'd already introduced Tracy Letts to Native Americans on his mother's family tree.

Now turning to his paternal roots, Tracy expected that we'd explore similar terrain.

His father, Dennis Letts, grew up knowing that some of his ancestors were members of the Muskogee Creek Nation.

And we did have a story for Tracy about those ancestors.

But first, we had a very different kind of story to tell.

It begins with Tracy's third great-grandfather, a man named Silas Barber.

We found Silas living in Texas in 1860, just months before shots were fired at Fort Sumter, which brought me back to a question I'd asked Sara.

Have you given much thought to how the Civil War may have affected your ancestors?

LETTS: Not at all.

(laughter).

Not given it any thought, never heard anything about Civil War history in my family.

GATES: Silas would've been about 38 years old at the time.

What do you think he did during the war?

LETTS: He did not fight in the war.

GATES: Okay, that's a good guess, please turn the page.

LETTS: Let's see, oh!

GATES: Would you please read the transcribed section?

LETTS: Fought on the wrong side.

“Confederate Company B 10th Regiment, Texas, Silas H. Barber, Private, age 38, enrolled on October 10th, 1861”" GATES: Your ancestor joined the Confederate Army.

LETTS: Well, that's too bad.

GATES: What's it like to learn that?

LETTS: It's a surprise because I've never heard Civil War associated with my family in any capacity.

GATES: Right.

LETTS: 38-year-old private in, in the Confederacy, sounds like a, just sounds awful.

Everything about it sounds bad.

GATES: What would your father say?

LETTS: Oh, he would, he would not have much patience with that.

GATES: As it turns out, Silas himself would be sorely challenged as a soldier.

In January of 1863, he was stationed at a Confederate fort on the Arkansas River when the Union Army attacked, supported by a fleet of gunboats.

The fort was completely overrun, and Silas found himself in a very unfortunate situation.

LETTS: “Prisoners at Camp Douglas, S.H.

Barber, Regiment, 10th, Texas, Company B. Where captured?

Arkansas Post.

When captured?

January 11th, 1863.” GATES: Your ancestor was captured.

LETTS: Good, good!

He should have been captured.

GATES: Did you ever think you had an ancestor who had been imprisoned?

LETTS: Oh yeah.

GATES: Oh yeah?

(laughter).

LETTS: I would've bet on prison for a lot of them.

GATES: But imagine what that was like.

LETTS: I wouldn't imagine that was, uh, any fun.

But, uh, yeah, good.

GATES: Silas was sent to a union prison in Illinois.

He would be exchanged after only a few months, but he did not return to the South unscathed.

In May of 1863, he appears in the records of a Virginia hospital where he was being treated for "debilitas," a Latin term for enfeeblement.

Also used to describe feelings of depression or melancholy.

Silas spent just over a month recuperating.

You want to guess what happened to him next?

LETTS: He was fine.

GATES: He went back to active duty.

LETTS: No, really?

GATES: He went back to active duty.

He was serious about the Confederacy.

LETTS: Silas, what were you thinking?

GATES: Why, why would he do?

I mean... LETTS: I, I, I, it's so mystifying to me why he would want to fight at all, why he would want to fight for the Confederacy, why he'd want to fight at 38 years old, and certainly after being imprisoned and suffering from melancholy and debilitas and enfeeblement.

I mean, why would you want to go back into battle?

GATES: Uh, you had a strange ancestor.

LETTS: Yeah.

He was, he was passionate.

GATES: He was passionate, that's right.

We don't know why Silas cared so much about the Confederacy, but as we looked into the records that his family left behind, we found what might be a clue.

His father, Tracy's fourth great-grandfather, was a man named Allen Barber.

And the 1830 census shows that Allen had a vested interest in the Southern cause.

LETTS: “Slaves, one female between the age of 36 and under 55.” GATES: Your fourth great-grandfather was a slave owner.

LETTS: Well, that sucks.

That's, uh, that's just terrible.

I, the Barbers are not impressing me.

GATES: Allen's father, your fifth great-grandfather, was a man named James Barber.

He died in 1842, and his will mentions that he owned two enslaved persons.

So, did you ever think about having ancestors who may have enslaved human beings on your family tree?

LETTS: Well, I, I have, I thought about it.

Sure, coming as I do from Oklahoma and, uh, meaning the southern part of the United States.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: Would I have thought it possible?

Sure.

So I'm, I'm disgusted.

I'm not surprised.

I'm like, “Ugh, the Barbers.” Maybe that's why I didn't know about 'em.

GATES: We now turn to the part of Tracy's father's family that he thought he knew better.

His Muskogee Creek ancestry, it's extensive and it contains one particularly intriguing individual, a man named Alexander Posey.

Alexander is Tracy's second cousin, four times removed, and the two seemed to have inherited some of the same talents.

In his day, Alexander was a renowned poet who chronicled the hopes of his people.

LETTS: “I pledge you by the moon and sun.

As long as stars their course shall run.

Long as day shall meet my view.

Peace shall reign between us two.

I pledge you by those peaks of snow.

As long as streams to ocean flow.

Long as years their youth renew.

Peace shall reign between us two.

I came from mother soil and cave.

You came from pathless sea and wave.

Strangers fought our battles through.

Peace shall reign between us two.” Nice.

GATES: What do you think of that?

LETTS: I think that's great.

GATES: What would your dad say?

LETTS: My dad would like that.

And he would like, uh, that there's a poet in the family, and a he'd like this a lot more than he liked these bastard uh, these, uh, these damn Barbers.

He'd like these Poseys a lot more than these Barbers.

Alexander is related to Tracy through his third great-grandmother, a woman named Sarah Posey.

Digging deeper, we were able to identify Sarah's grandmother, Tracy's fifth great-grandmother, who was born on Muskogee tribal lands in the 1780s.

Seeing yet another branch of his native roots laid down in such detail was deeply moving to Tracy, and he was eager to share the news with his children.

LETTS: My son is six years old, he's in the first grade, and he just had his first lesson in his first-grade class about Indigenous people.

GATES: Oh, wow.

LETTS: And he came home, and he started telling us about the lessons that he had learned.

And my wife said to him, you know, we think... GATES: Mm-hmm.

LETTS: ...that you actually, you yourself come from a, a family line that includes Indigenous people, and he reacted strongly to that.

I mean, he, there was a moment of, "Oh really?"

Man, again, we love it when it, we can relate it to ourselves.

GATES: Sure.

LETTS: So the fact that I can now take this to him and say, you in fact do, and here, not only do you, but here are their names.

GATES: Your fifth great-grandfather is his sixth great-grandfather.

LETTS: Right.

GATES: Yeah, that's pretty cool.

LETTS: That's very cool.

GATES: The paper trail had run out for each of my guests.

It was time to show them their full family trees.

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

LETTS: Whoa.

GATES: Now, filled with names they'd never heard before, for each, it was a moment of awe.

HAINES: Oh my gosh.

LETTS: That's a lot!

(laughter).

It's fantastic.

HAINES: This is the best gift I've ever been given.

GATES: Offering the chance to see themselves in a new light.

LETTS: Look at all these people, look at all this history, it's amazing.

HAINES: This is just so crazy.

I have identity.

GATES: Big time, deep American... HAINES: Deep American identity.

GATES: Yeah.

My time with my guest was running out, but I still had one surprise to share.

When we compared Tracy's genetic profile to that of others who've been in the series, we found a match, evidence of a distant cousin he never could have imagined he had.

LETTS: Okay, I'm nervous.

GATES: Okay, you ready to meet your cousin?

LETTS: Sure.

GATES: Please turn the page.

LETTS: Oh, that's fantastic.

(laughter).

GATES: Tracy shares a long segment of DNA with actor Julia Roberts.

They also share an experience.

The two worked together on the film version of “August: Osage County.” Tracy's breakout hit.

LETTS: And I adore her.

She's just great.

We, we had such a great time.

Uh, she's just such a lovely person.

That's amazing, that's great.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Tracy Letts and Sara Haines.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of “Finding Your Roots.”

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep6 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. heads west to map the family trees of Sara Haines and Tracy Letts. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: